Programme design and proposal writing rests upon a mutual understanding and trust between colleagues with expertise in PMSD and those with expertise in business development and fundraising. It is a crucial use case for PMSD, because it determines the resources, conditions and evaluation criteria that will shape a PMSD project throughout its lifecycle. It requires a strong team with a wide range of skills sets working closely to translate ideas across contexts.

The following guidance uses Practical Action as the example organisation but is appropriate for anyone wishing to use PMSD.

Who is this guidance for?

People in a range of roles are involved in programme design and proposal writing. This guidance is meant to support a full range of people, including:

- Senior PMSD experts

- Change ambition leaders

- Thematic Leaders

- Business development staff

- Recruiters

- Country directors

This guidance is structured around four parts:

Understanding donor requirements sets out a simple process for assessing the fit with what the donor actually wants and strategies for improving this alignment.

Preliminary analysis of market system opportunities and challenges describes how you can use market assessments to strengthen your proposal.

Translating and communicating how PMSD meets the donor’s evaluation criteria provides insights on the language to use to different types of donors.

Detailing organisational factors helps you understand how you can sell your team and your organisation to the donor.

Part 1: Understanding donor requirements

Key people involved:

- Business development staff;

- Senior PMSD experts;

- Change ambition leaders,

- International Operations Managers

- Thematic Leaders

Projects can be funded through a wide range of mechanisms, but the assumption for this use case is that Practical Action is responding to an explicit call for proposals from a donor. In this environment, PA will invest its own resources in preparing a proposal that competes with other organizations’ proposals to get funded.

The first step therefore is to critically assess the donor’s priorities and requirements, to determine if they align well with what PMSD can offer and overall PA strategic fit. Not every proposal should integrate PMSD – it’s important to be realistic. The table below differentiates between “ideal fit”, “compromise” and “poor fit” scenarios, and includes signals of each.

Ideal Fit

- Longer timeframe (5 years and beyond);

- Focus on sustainability of outcomes, in terms of changing systems and behaviours of actors;

- Private sector partnership as means to achieving scale;

- Acknowledgement of trade-off between control over direct impacts and achieving wider indirect impacts;

- Acknowledgement of uncertainty and the need for learning and adaptive management.

Compromise

- Medium timeframe (3-5 years);

- Brief mentions of sustainability, with high outreach targets;

- Expectation of direct support to beneficiaries as well as private sector engagement;

- Request for detailed output and outcome projections;

- Mention of systemic change but poorly defined.

Poor Fit

- Very short timeframe (less than 3 years);

- Very high outreach targets with high attribution via direct delivery;

- No mention or interest in private sector engagement;

- Fixed budgets with highly specified activities and output focussed targets.

It is likely that the majority of tenders or request for proposals (RFPs) will fall somewhere in the middle category – compromise. In these scenarios, you will need to go over and above the minimum requirements of the tender, and possibly push back to challenge some of the assumptions or conditions written.

The next step is to analyse the key evaluation criteria by which the donor will assess proposals. Ideally, these criteria are made explicit and available. However, it is also useful to draw on internal experience with the particular donor – to reflect on past proposals and recent awarded projects. Are there unwritten or implicit ideas, priorities or values that this particular donor assumes will be in a proposal?

Finally, it’s useful to put together a team with a mix of backgrounds meet to critique the key assumptions within the tender document:

- How clear or accurate is the donor’s portrayal of the market systems in question? Do they already propose very specific sectors or sub-sectors, or is this open to the proposals?

- How realistic are the outreach numbers that the donor has suggested? How specific is the target group (characteristics, geography)? Are there tensions between these numbers and sustainability? How realistic is it to reach that group in a meaningful way?

- What jumps of logic are made in the theory of change? Which might we want to challenge or push back on?

- What statements about the team or team leader are made in the tender? What kind of project team would we need to propose? What does that require from a recruitment perspective?

Part 2: Preliminary analysis of market system opportunities and challenges

Key people involved:

- Country directors

- Project staff

- Change Ambition leaders

- Thematic Leaders

Depending on the size of the project, the prior in-country experience of Practical Action in the region in question, and the priorities of key leaders, it is likely that some preliminary fieldwork and analysis will be done to prepare a proposal. In this way, some of the crucial assumptions from the donor’s tender document can be tested, and additionally, Practical Action can refine and sharpen its proposed approach.

There are three important tools that can help to structure this process:

- Market selection;

- Preliminary market mapping; and

- Theory of change.

Market System Selection

The degree of flexibility and control over Market System Selection varies drastically depending on the donor or the tender document. Regardless of whether it is an open decision, or if specific market systems have been prioritised by the donor, it is worthwhile to independently assess and score potential market systems. This way, there is a basis for the market systems you propose or for pushing back on the donor (if the analysis shows a better alternative to the ones they suggest); and there is an evidence trail for future reflection if the situation changes drastically and the project needs to switch market systems.

In general, market systems selection for proposal writing will be a much faster exercise, drawing on whatever internal resources are available. If possible, it can be strategic to propose a portfolio of market systems to engage within a given project. This creates space for some learning and adaptation during implementation, and it can start to signal to the donor how the project may work on particular production-focussed market systems (e.g. particular crops or livestock in the case of agriculture), but also on crucial supporting market systems (e.g. transportation services or extension services or skills/human resources).

Additional resources:

Preliminary Market Mapping

Where there is a clear single market system that will be at the heart of a PMSD proposal, it is advantageous to invest in a Preliminary Market Mapping process. This will provide a quick sketch of the structure of the market system, the key players involved and some of the systemic issues that the programme may need to focus on. In doing this, it presents you with evidence of a well thought out rationale for what you plan to do and who you will work with which will strengthen your proposal considerably.

When using Preliminary Market Mapping for a proposal, a key step is to identify and analyse a few key market actors. Field teams should make the effort to meet with a key market actors to understand how the actors see the problems in the market system and their own interest and ability to take action to create change. From a few strategic meetings, the team can understand market actor incentives and capacities, and therefore differentiate PMSD from other proposals. Ultimately, the individuals who own or lead key organisations and businesses will be the ones that determine what level or scale of change is possible, and its long-term sustainability.

Vision / Theory of Change

To be compelling and credible, a PMSD proposal will need to communicate a vision for market systems change, and a theory of change for how the project will facilitate the process to move the market system in that direction. There is a tension in that it is difficult to predict the outcomes of a participatory process, but it is crucial to find a compromise in order to develop proposals that get funded in the first place!

The best sources of insight and information on a feasible vision will come from direct interaction with individual market actors. Ideally, this happens through a shortened version of the Preliminary Market Mapping. This should also include the perspectives of marginalised actors (e.g. small farmers, women, informal workers), their opportunities for improved knowledge, skill and income, as well as greater power to make choices and determine the directions of their lives.

The vision is more than a simple ‘vision statement’, it needs to be something that gives a picture of:

- The future structure of the market system – key players, relationships and roles. This can be demonstrated in a companion market map that highlights the proposed changes.

- The future flows of finance and products in the market system – drawing on the sustainability matrix which asks: “Who Does, Who Pays” presently and in the future.

- How the changes in the market system relate to improved power, decision making, income and other outcomes for poor and marginalised groups.

The companion to this detailed vision is a theory of change, which links PMSD interventions and activities to the longer term vision for a higher performing market system.

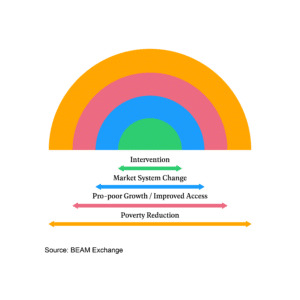

Figure: different levels for a vision

The key elements of such a theory of change include:

- A description of the long term goal;

- An explanation of the context;

- An explanation of the sequence of change that is likely to lead to that goal;

- A description of the assumptions between each link in the sequence of change;

- A conceptual diagram which outlines the key causal links from program activities through to impacts.

What is crucial for PMSD is to articulate how the ownership of changes by market actors themselves is linked to the long term sustainability of the change. Projects are likely to be focussed on lower cost ‘light touch’ interventions – starting from Participatory Market Mapping but extending to work 1-on-1 or in small groups with key market actors.

Part 3: Translating and communicating how PMSD meets the donor’s evaluation criteria

Key people involved:

- Business development staff

- PMSD senior experts

- Change Ambition leaders

- Recruiters

- Thematic Leaders

The biggest challenge in writing a strong PMSD proposal is taking the market systems insights from the field and communicating them to donors in language and terminology that is easily understood. This part requires trust and collaboration between PA staff working in very different contexts.

It is useful to differentiate the approach to this task depending on the nature of the specific donor or funding opportunity. The degree of translation will differ greatly if the donor has experience and knowledge of market systems development (MSD) in general, versus where they do not. This will also affect the positioning and competitiveness of PA’s PMSD offer in relation to other organisations.

Donor without MSD experience/exposure

Many donors may not know about, or be familiar with the language of MSD. This situation requires focusing more on the key principles and ideas of PMSD, and avoid getting caught in the jargon. A key strategic decision is whether to spend valuable proposal space introducing and explaining PMSD, or whether to simply translate PMSD into terms that the donor will understand.

Some tips and examples for how to do this include:

- Sustainability: emphasise why it is so important to have buy-in and ownership of changes from market actors, and how this translates into benefits for poor/marginalised groups.

- Facilitation: Find ways to explain facilitation that make it clear this extends far beyond holding meetings, and is actually about fostering relationships and new ways of thinking and leads to local actors driving and owning change

- Systems thinking: Emphasise that an understanding of the system helps identify interventions and partnerships that can change deep rooted problems for the benefit of marginalised groups and others in the whole system.

Donors with MSD experience

When developing a PMSD proposal for a tender that explicitly asks for an MSD approach, a different tactic is required. In this scenario, the communication challenge is to demonstrate that (a) PMSD is connected to, and draws from MSD best practice; and yet (b) it has distinctive differences and advantages that make it worth funding over ‘mainstream’ MSD.

The key differentiators for PMSD compared to traditional MSD are:

- Empowering marginalised groups to be active participants in a market development process, rather than just passive beneficiaries of change. PMSD changes the power relationships and dynamics, shifting perceptions within the market system itself to see previously marginalised people as legitimate market actors themselves.

- Involvement of market actors in the analysis process, leading to deeper engagement, collaboration and ownership of market development and building system resilience.

- Collaboration between market actors, building trust and further strengthening the resilience of the system.

- Emphasis on the capacity of project staff as facilitators. Intensive training, mentoring and capacity building helps to build a local market systems facilitation resource.

- Seeking solutions from market actors and getting leadership and commitment to solve challenges among themselves.

Part 4: Detailing organisational factors

This section draws heavily on two key resources:

- Guidelines for good market development program design: A manager’s perspective

- Deepening the Relationship: a step-by-step guide to strengthening partnerships between donors and implementers in MSD programs

Increasingly, the field of MSD is recognising that the crucial differentiators when it comes to strong programme design and implementation relate to organisational factors, including: the project consortium and implementing team structure; staff backgrounds and experience; the team leader; the learning culture; and use of evidence for adaptive management. For a PMSD proposal to be competitive, particularly where donors know and care about these determinants of implementation success, it is useful to integrate these considerations.

- Focus on the team: Consider the individual and team skills needed for a quality PMSD programme: (a) analytical mindset to understand root causes; (b) specialist insight; creativity to come up with tailor-made solutions; and (d) ability to learn and adapt based on evidence and feedback. Some PMSD expertise is needed, but more important is that a core group can think systemically, and work together in a facilitative way, learning as they go. Emphasise diversity of team composition along multiple dimensions: gender, race, academic background; and strategies for developing an inclusive team culture focused on learning.

- Focus on team leadership: The team leader needs to have the above skills mix, plus the leadership ability to set a learning culture, mentor diverse project staff, and manage the relationship with the donor during implementation. Long, technical CVs do not equate to good MSD leaders, so internal hiring processes that assess these capacities of team leaders can go a long way to convincing the donor that the team lead is the right person for the project.

- Strength of consortium members: For larger bids, PA may be one of several partners in a consortium. It is crucial to understand the expectations for PA’s role in implementation and how PMSD is positioned within the consortium: Will PA lead the facilitation? Or train and mentor local NGOs? Or provide technical expertise on targeted assignments? The proposal needs to argue for the coherence of consortium partnerships in terms of specific roles, responsibilities and authority; strengths of members; value addition of each partner; as well as history of relationships between organisations.

- Project management ability: It is no longer enough to simply say ‘adaptive management’. Discerning MSD donors will want to see proof or track record of adaptive management. Emphasise what ‘adaptive management’ means in practice and how information, management and decision making procedures proposed will deliver that ‘adaptiveness’. Some key good practices include an internal learning (MEL) system that draws lessons from and for all experts in the project, and regular intervals (i.e. quarterly review meetings) for internal discussions to reflect on findings from the field, and make strategic adjustments. Research should be conducted by programme staff rather than externally funded consultants where possible to build internal capacity, and relationships with market actors.