Participatory Market Systems Development (PMSD) aims to address systemic problems so that markets work more effectively for marginalised groups, providing more lucrative and fairer opportunities. It does this by modifying the incentives and behaviours that determine how market actors act.

Central

Central to achieving this are four principles: Facilitation, Participation, Systems Thinking, and Gender.

Throughout the PMSD toolkit, you can find examples of the “Principles in Action” – embedded in specific guidance, or in case studies of PMSD from the field. The principles can be applied in different ways in different contexts with different weights put on each of them.

By using these principles, project teams can ask themselves reflective questions at regular intervals (e.g. at quarterly team meetings; or as part of After-Action Reviews for particular activities or interventions). A few examples of these types of questions are suggested below:

Systems thinking

- How do we distinguish between the symptoms and deeper causes?

- What are we learning about how the system is working, regardless of our attempts to change it?

- What are the most important relationships, and how are they changing?

- What examples are we noticing of people who are positive deviants (going against norms)? What can they teach us?

Participation

- How is the position of marginalised groups changing?

- How do market actors treat members of our target group when we aren’t around to watch or intervene?

- What examples do we see of marginalised groups gaining knowledge, relationships or bargaining power?

- What examples of trust developing between market actors do we see and is this leading to collaboration to solve problems in an inclusive way?

Facilitation

- How do the market actors perceive our contribution to creating change? How would they describe our role?

- What are the most important behaviour changes we are supporting and encouraging in the market? What tactics are we using to influence those changes?

- How confident does our team feel about playing a facilitator role? What can we do to boost skill and excitement for this?

Gender

- What behaviours and norms do we observe which are restricting opportunities for women?

- Are there examples of women making themselves heard and influencing market development activities? What is the underlying context behind this?

- Are there examples of women gaining access to assets, services or opportunities?

- How do other market actors perceive the involvement of women in markets?

“We interpret systemic change to be when new and improved behaviour of permanent market players is sustained beyond the life of the project, and change is manifested beyond the market players associated with the project.”

ILO The Lab

Principle 1: Systems Thinking

The market is a system in which multiple actors interact with each other and the cause of problems affecting any actor (e.g. a producer) may come from any part of the system. Programmes that only focus on one part of the system, and which fail to address the interconnections with other parts of the system, run the risk of failure and doing harm. Understanding the state and the dynamics of the wider system is critical to ensuring that priority is given to the issues that will have the greatest impact on improving inclusivity and effectiveness. PMSD does this through market mapping and deep analysis of root causes of problems. Often this shows us that the underlying problems are not the ones that seem to be immediately obvious but instead they are distant from the people we are targeting – for instance in enabling environment issues such as Government behaviour, competition or gender norms.

Principle 2: Facilitation

Rather than intervening directly to solve an immediate problem, PMSD aims to create incentives for market actors (including producers, workers, companies and Government) to change their behaviour and solve problems themselves. Facilitation includes a wide range of tactics – far more than just organising and running stakeholder workshops. Depending on the barriers faced by an individual actor, PMSD projects may use data, stories or role models to convince people to do something differently. This might include building capacity through technical support or linking to experts; and in some cases through the use short-term subsidies to decrease the risk of trying something new (e.g. cost-sharing initial start up costs for new business activity that has a pathway to economic sustainability). Practical Action always aims to avoid becoming a market actor itself. In this way, we hope to achieve systemic change. PMSD includes guidance on facilitation and strategies to enable effective engagement with businesses and other actors.

Download the two resources below to take a deep dive into what it means to be a market facilitator.

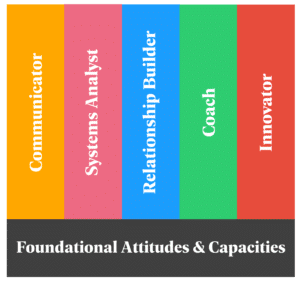

- The five roles of a market facilitator: System Analyst, Coach, Communicator, Relationship Builder, and Innovator. Fill out the tables to assess your individual capacity along each of the five roles.

- Read case studies of good and bad market facilitation: these provide additional context on what it means to apply each role in a real-life project example.

Principle 3: Participation

In PMSD, it is the market actors themselves who determine the course of action to be taken and who lead the analysis for this. PMSD’s unique contribution is to integrate marginalised actors (e.g. women, youth, farmers, small producers) to participate in this process and to influence others. This can change power dynamics, improving their ability to engage with and negotiate with business. PMSD also supports the development of relationships between market actors from across whole sectors, through a multi-stakeholder process that can build the resilience of the market system.

The degree and type of participation involved in any particular project will vary. In some cases, interventions may start with a more narrow focus on one or two business partners because that is where the immediate opportunity to start something lies. In such cases the principles can still apply and opportunities to broaden participation can be looked at as the initiative progresses.

Principle 4: Gender

Practical Action’s vision of a fairer more just world will not be achieved without gender equality. Markets support progress towards this goal and also present an opportunity to achieve other positive change:

- Greater, fairer inclusion in markets presents opportunities for women to increase income and gain control over assets. As well as a basic issue of equality, it has been shown numerous times that greater income in the hands of women, leads to stronger household developmental benefits (e.g. improved nutrition, better education etc).

- An increased number of women in economic leadership roles (e.g. as entrepreneurs) can challenge gender stereotypes and cultural norms that hold back equality.

- Markets present a forum in which women can develop voice and agency and influence business and policy makers, shifting power dynamics.

- Markets can improve the resilience of vulnerable women by improving income, increasing control over assets and strengthening agency.

For such outcomes to be achieved, market development programmes need to be purposefully designed with gender in mind. Typically programmes can deal with gender in several different ways, as illustrated by this simplified gender ladder:

Gender blind

Programmes that are gender blind ignore gender differences in markets. They may profess to be ‘neutral’ but the presence of existing inequities means that women are unlikely to significantly benefit and may actually end up worse off. For instance, market development interventions that make a traditionally women-led role more lucrative, can result in men coming in and taking over if the power dynamics that underpin this are not understood and addressed.

Gender sensitive

Programmes that are gender sensitive are based on an understanding of gender differences in markets. This is used to design interventions that ensure that women benefit. However, this does not challenge existing inequities and is based on pre-existing gendered distribution of roles in the market. In practice, interventions may include the training of women, increasing access to inputs and services or facilitating market linkages.

Gender transformative

Programmes that are gender transformative purposefully set out to challenge underlying inequities in the market system, tackling power relations to ensure that more income and influence ends up in the hands of women – and the market moves towards being more equitable. In practice, interventions may focus on increasing the participation of women in decision making at all levels. This supports women to move into new roles that challenge gendered economic norms; reconfigures how services are designed and delivered so that they respond to women’s needs; and increases women’s control over assets.

What sort of markets work for women?

Not all markets are the same. The type of market will determine the level of opportunity to support gender transformation.

Women are usually found in low value markets (e.g. staple food crops) and are usually in the least lucrative, most precarious occupations (e.g. as producers). In such markets our aim should not be to simply increase the number of women who are present in poorly paid, low status roles. Instead, we should be aiming to either: improve the conditions experienced in those roles so that they are better remunerated and have higher status; or we should remove constraints so women can access roles offering more lucrative opportunities. In practice, this could mean more women developing roles as processors or traders or as service providers – changes that would create a win-win, providing better opportunities directly to the women in these roles and delivering gender sensitive services benefiting other women.

High value traditional export crops get a lot of attention with global companies keen to improve inclusivity. However, these markets are usually dominated by men and women will often lack the skills, assets or networks to compete. In programmes that target these sectors, questions should be asked regarding how realistic it is to expect significant gender transformation. In contrast, large numbers of women are often found in informal market systems. This provides an opportunity to improve how these markets work for women, including supporting a gradual shift to formality.

Likewise, in new developing high value markets (e.g. organic or local source markets), there can be a unique opportunity to build women’s participation from the onset. These sort of markets will come with high quality standards and facilitating the development of services that help women reach these standards can often be an important strategy to cementing their position in the market.

Practical Action aims to mainstream a Gender Transformative approach into all interventions. This means addressing structural inequalities pertaining to division of labour, access to and control over resources, and decision-making.

At Practical Action, we strive to support Gender Transformative approaches which can be targeted through market-based programming.

There may be some instances when, because of funding or other aspects in the local context, it is only realistic to be Gender Sensitive. But, it is critical that our programming is never be Gender Blind.

To achieve this, programmes should aim to achieve two types of outcomes which can provide the basis for indicators:

- Facilitating equal access to resources for women;

- Enhancing women’s role in decision making at all levels and strengthening women’s agency to make choices and influence how markets operate.

There can be a two-way relationship between these outcomes: more agency for women can lead to improved access to and control of resources and in some circumstances, the reverse can also be true. Taking this approach requires engagement with issues traditionally seen as being about markets – for instance, access to finance and value chain linkages. But it also requires a recognition of non-economic factors such as educational levels of women, which are often lower because of years of discrimination, and informal rules and norms that shape markets and women’s role in them. Gendered norms for instance will influence the roles that women play: certain roles are considered ‘men’s’ or ‘women’s’, for example, the unfair distribution of care work means that women are time poor, limiting their ability to engage in economic activities. If we are to have an impact on gender equality, these structural inequalities need to be addressed.

Guidance on how to support these outcomes is provided across all of the Tools in the Toolkit.

Other useful resources:

- Women’s Economic Empowerment: Pushing the frontiers of inclusive market development, LEO Brief, USAID

- Integrating gender into inclusive market development, Christian Aid

- Rapid Care Analysis Toolkit, Oxfam