The impact of COVID-19 on the energy-use of refugee households in Rwanda

In Rwanda the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly affected the ability of refugees to pay for energy services, to fix problems, and to access new products. But those with access to energy have also felt safer, more productive, and more connected to their families and to the outside world.

“After a closure of all schools that was followed by a countrywide lockdown, all my children: Celine in primary 6, John in primary 3 and Henriette in primary 2 are happy to continue their studies at home… [They do so] through a radio learning program for primary schools that was launched by the Rwanda Education Board in April 2020. My radio was [also] an efficient way to raise awareness and fight stigma arising from this COVID-19 pandemic. Today, we are aware that we should not shake hands anymore”.

Senyana, Nyabiheke refugee camp May 2020

Senyana fled from internal conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo and came to Rwanda, where, like many of her fellow residents in Nyabiheke refugee camp, Senyana has found that life has changed dramatically since the pandemic struck Rwanda. Restrictions on her freedom of movement, and price increases for food and other basic commodities have hit her – and her family – hard. But like many of the lucky minority in the camp who have access to power – she has found her radio to be a lifeline.

Although life is still formidably hard, refugee camps in Rwanda have begun to improve access to energy – and opened up a range of subsequent developmental benefits – over the last few years. Nearly 60% of people still have no access to power for lighting or charging a phone and only one in four has access to anything but the most basic fuel with which to cook. But several humanitarian and development programmes have encouraged energy businesses to expand their operations into refugee camps, solar street lighting has come to Nyabiheke, Kigeme and Gihembe camps, and residents have increasingly been able to access new energy products and services for cooking, lighting and powering their homes. Meanwhile, humanitarian organizations have begun the process of ‘greening’ their existing operations by monitoring their consumption and producing a detailed assessment of opportunities to switch to renewable energy.

But then came the pandemic.

Little is known about how COVID-19 has changed the way that refugee households use energy. But this blog reflects on the learnings that the Renewable Energy 4 Refugees (RE4R) project collected in three camps in Rwanda between April 2020 and December 2020, both before and during the pandemic. How have pandemic restrictions changed the way that people use and pay for energy? How is access to energy helping (or hindering) refugees’ ability to cope during the pandemic? And can we draw out any lessons to ensure that the pandemic’s effects are not prolonged or debilitating?

A panoramic view of Gihembe refugee camp. Credit: Edoardo Santangelo

COVID-19 and Rwandan refugee camps

Officially, Rwanda has had over 19,000 cases of COVID-19 and 265 deaths, but the likely rates are much higher since testing has been heavily centred on Kigali. Although the camps have reported cases, little is known about the rates of infection or transmission. Rwanda currently hosts nearly 150,000 refugees (largely from DRC and Burundi) and has six refugee camps which together house the majority of these displaced people.

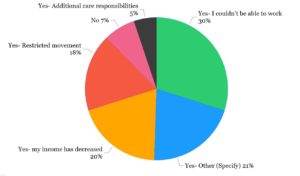

Figure 1: Has anything changed in your personal circumstances since COVID restrictions were put in place? Source: non customer monitoring survey, October 2020. Based on 97 people (71% female) split across the three refugee camps.

Refugees are particularly at risk from the health issues associated with COVID-19 because they often have limited access to water, sanitation systems or health facilities (although the fact that 40% of refugees are under 18 years old perhaps counts in their favour) and also because people are closely clustered together allowing COVID-19 cases to spread quickly. But, as Kurt Tjossem, regional vice president for East Africa at the IRC noted recently, the crisis is not only about health; the effects of lockdowns have perhaps been more significant than the health crisis for those affected by conflict and displacement¹.

Globally, it has been suggested that as many of 86% of refugees and migrants are in need of extra help since the COVID-19 crisis began, but only 21% report receiving additional assistance. In Rwanda, full lockdowns between March and May, and again at the time of writing, have primarily affected Kigali, but other related restrictions on the movement of refugees, on the type of operations humanitarian agencies are allowed to perform, have increased the price of food and fuel, reduced remittances from relatives, and led to job losses that have all impacted on ‘normal’ life for those in camps. Figure 1 highlights some of the personal changes that have affected refugees in Rwanda since the pandemic took hold.

It shows that almost all of those surveyed – 74% of whom were single headed households and would have been classified by UNHCR as ‘vulnerable’– experienced significant personal challenges with the most prevalent being the inability to work, decreased income, restricted movement, price increases for food, and an overall increase in debts.

Light in the dark

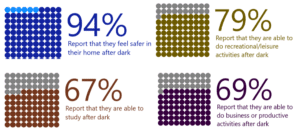

Practical Action’s longitudinal surveys in Rwandan refugee camps show that those with access to energy products have reaped significant benefits. This is illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Benefits of access to solar home systems

Of the 84 refugee households with solar home systems (SHS) who were surveyed, the average reduction in spending on candles was 76% and the average reduction on spending on non-rechargeable batteries was 81%². These benefits are not unique to the pandemic, but they have been placed into sharper focus during periods in which curfews have meant a larger than normal amount of time spent inside the household. A number of survey respondents mentioned that not having to rely on purchasing candles and batteries during the pandemic has been extremely useful since supplies have been limited, and there are greater concerns about theft³.

Overall 52% of those with a SHS felt that it had supported them to a ‘very great extent’ or a ‘great extent’ (with another 21% suggesting it had helped to “a moderate extent”) during the pandemic in particular because of the feelings of connectivity that could be generated from listening to the radio (hearing more about the situation and the national issues) and because household lighting allowed families to spend time together in evenings when movement is restricted⁴. The interview with Theogene Ndatimana, a Practical Action Field Coordinator is emblematic of this.

For others, access to energy – and in particular the installation of streetlights – has made them feel safer; and helped to reduce worries about theft and to improve feelings of safety when moving from households to toilets at night. Given the limitations on movement that have been imposed, and the fact that more time is being spent in the camp overall, this is particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The lights are shining bright in the night. As the camp leaders we used the light to go through the camps during the lock down to supervisor there is no one from the affected camps that has visited us, and it was easy to check on who is following the COVID-19 Guidelines.”

Negative impacts of COVID-19 on energy access

As pressures on income have increased, restrictions on movement have limited the ability to travel, remittances have reduced, and already precarious jobs have been lost, it appears that many refugee households have reduced ability to pay for energy services, as illustrated in Figure 3.

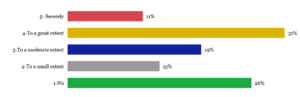

Figure 3: The extent to which COVID-19 has impacted ability to pay for SHSs Source: Outcome monitoring survey 3, October 2020, based on 84 respondents (60% female) across the three refugee camps

Figure 3 shows that 61% of respondents felt the COVID-19 crisis had significantly affected their ability to pay for a solar home system. Such findings are consistent with broader results in the off-grid sector – for example 60 Decibels shows that between 47-55% of surveyed customers reported that payments were “a heavy burden” or “somewhat of a burden” in the immediate post-COVID environment rather than 32% beforehand⁵. The fact that the numbers in Rwandan refugee camps are slightly higher than the broader sector should perhaps not be surprising given the additional vulnerabilities – and low incomes – of most refugee households.

At the same time as they are feeling pressure on income, refugees have also seen the number of available energy products and services decrease. The liquidation of the stove and fuel company Inyenyeri in April 2020 – which had been operating in Kigeme camp with UNHCR support since 2016 – due to its “inability raise the capital required to thrive” is part of this. But a number of other energy suppliers have found it more difficult to enter the camps and sell products. Existing suppliers have been able to access the camps (with difficulty), but for new suppliers access has been nearly impossible. And those who have been able to enter the camps have remarked on a downturn in the number of purchasers buying their products.

Perhaps most frustratingly, refugees have also found it harder to fix technical problems that have developed with their energy products. All SHS sold in the camp are under warranty, which means that the suppliers are responsible for fixing technical problems. And the importance of this warranty has become clear since as many as 44% of those who purchased solar home systems have experienced some technical problems since the date of purchase⁶. The majority have been able to resolve these problems without significant barriers, but for those that haven’t, the primary reasons have been due to technicians being unable to access the camp, and because parts have been unavailable (both issues directly related to the pandemic). Globally – anecdotal evidence suggests that camp managers often consider energy suppliers insufficiently ‘essential’ to allow access in the COVID-19 context.

What can we learn?

It is difficult to read too much into the experience of just three camps. Even within Rwanda, contextual differences between the three sites are significant, and this alone should caution us about extrapolating too broadly beyond the observations outlined here. Nevertheless, the experiences being reported in Rwanda should lead to serious concerns for all those tracking the progress of the nascent humanitarian energy sector.

The additional vulnerabilities that have been created by the pandemic (loss of income, jobs, movement, remittances etc) and the high levels of difficulty reported with current payments, lead to uncomfortable questions about whether reduced ability to pay for energy services will lead to problematic coping strategies (for example reducing expenditure on food to keep up payments on energy products – something I will consider later in this series). The President of the World Bank has warned that an additional 60million people will probably be in “extreme poverty” as a result of the pandemic and those at the most vulnerable end of the spectrum are among the most likely to be hardest hit.

But for those who have access to energy in the camp, it is clear that there have been considerable benefits – and two particularly stand out. Firstly – refugees feel safer – something that is clearly important when concerns about safety and theft are on the rise and when movement is restricted and controlled. Secondly – access to energy has provided ‘connection’ – both expanding the time one is able to spend with the family – and improving the quality of that time, as well as allowing refugees to understand the context of current measures – how their own situation is echoed within wider society beyond the camp. Refugees inside the Rwandan refugee camps have continued to demonstrate resilience, fortitude and an enduring ability to find new ways to meet daily challenges. Access to energy has provided the means to contextualise the current challenges – and to meet these challenges head on.

- 1. Abdi Latif Dahir, “‘Instead of Coronavirus, the Hunger Will Kill Us.’ A Global Food Crisis Looms,” The New York Times, April 22, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/world/africa/coronavirus-hunger-crisis.html

- 2. Outcome Monitoring Survey 3, October 2020

- 3. Contextual Review of Kigeme refugee camp, Theogene Ndatimana, December 2020

- 4. Ibid.

- 5. Reassuringly, 60 Decibels also found that this % was decreasing over time and heading back towards levels reported pre-COVID.

This blog is the first in a series of three which will examine the impact of COVID-19 on how refugees in Rwandan camps are using energy. Later pieces will examine the impact of the pandemic on refugee businesses and micro enterprises, as well as energy access companies working in the camp.