Introduction

The human body needs fuel to function. From this most basic survival need comes the term ‘food security’. In its simplest definition, food security denotes regular and continual access to sufficient, nutritious, and safe food. This is essential for our individual wellbeing. On a global scale, food security means ensuring the availability of food for almost eight billion people. For this supply to be sustainable, its production should cause the least destruction and depletion of our natural resources possible.

Factors affecting global food security are plentiful and complex. A key word mentioned above is availability: despite global food production being sufficient to feed our entire population, one in every ten people cannot afford to eat a basic healthy diet[i]. This inconsistent access food is rooted in many complex and entangled issues: climate change, access to water, supply chain disruption, unsustainable agricultural practises, competition for land and many more.

In 2020, 768 million people were considered to be severely food insecure – an increase of 118 million from 2019[i]. That equates to one in eleven people facing hunger. The pandemic brought widespread disruption to normal food supply chains and production processes. But since then, global inflation has hit new records, we’ve seen a cost-of-living-crisis sweep the globe, increases in food bank dependency (even in the world’s richest nations) and frightening surges in temperatures. Understanding what causes food insecurity is paramount to our survival, and for ensuring the food system works for everyone.

What causes food insecurity?

Armed Conflicts

War and civil conflict are the biggest cause of hunger globally. With disruption to normal food production processes and businesses struggling to operate, both household income and food supply chains are affected. War can devastate agricultural land (or discourage access to it through landmine usage in some circumstances). The workforce is typically disrupted as people flee to safety or enlist into military services, and the economy generally becomes unstable to due military intervention or changes of government.

The Climate Crisis

As the frequency of adverse, extreme weather events continues to increase, climate change is fast becoming a key contributor to food shortages. According to a report by the World Meteorological Organization, weather-related disasters have increased five-fold over the last 50 years[i]. Floods, droughts, desertification, wildfires, and erratic rainfall patterns are taking their toll on harvests across the world. Disrupted seasons are also bringing an increase in pests and new crop diseases, all of which affect farmers’ ability to earn a reliable income. Among the world’s poorest people, 75% are reliant on small-scale agriculture as a livelihood; the climate crisis is pushing these vulnerable communities further into poverty and hunger. Meanwhile, consistent poor harvests can have a significant impact on food prices, affecting affordability at a national and even global level.

Economic instability

Major international shake-ups, the availability and market value of essential commodities, wars, pandemics – these are all examples of ‘shocks’, or circumstances that affect global economic stability and the value of currencies. For example, Russia’s attack on Ukraine affected the price of wheat (the region being an important producer of the grain), a staple ingredient for many nations. Inflation steadily pushes up the price of food, but when economic shocks happen, it can lead to hyperinflation making essential sustenance expensive for many.

In addition to these three major causes, there are many other factors affecting our ability to grow, transport and pay for food. These include: commercial, intensive farming methods which deplete soil nutrients and affect biodiversity (- often a natural defence system against pests and diseases); population growth and the pressure this puts on natural resources needed for food production; a decline in the number of people choosing agriculture as a profession; and a reduction in the land available for food production because of competing land usage (e.g. arable land being utilised to grow cattle feed or mine for minerals instead).

How does water scarcity affect food insecurity?

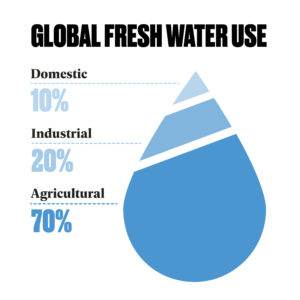

Water is necessary for crops and livestock. We can’t explore food insecurity without discussing the management of water in farming and the landscape. Around 70% of the planet’s available water is currently used for agricultural purposes, this is expected to increase by 20% by 2050[i]. According to a report by the Food and Agricultural Organization in 2022, increasing demands for water are likely to become the biggest cause of food insecurity and hunger within the coming two decades.

In many regions of the world, climate change has disrupted seasonal rainfall patterns, causing both prolonged droughts and devastating floods. In places like Zimbabwe for example, this has resulted in failed harvests, with crops failing due to inadequate water or being destroyed by floods, and fertile top soil washed away, followed by severe food shortages.

How can food security be improved globally?

While there is clearly no easy solution to tackling the tangled web of issues and myriad factors which put food on our plates, tangible action can be taken on at least some aspects of the problem.

Regenerative agriculture

One area where change is possible is agriculture: we need sustainable farming and food systems which protect biodiversity and ecosystems, and do not degrade soil or pollute water sources or landscapes. Globally, agriculture is responsible for 37% of human-led greenhouse gas emissions[i], 80% of the world’s deforestation[ii] and is a major catalyst of biodiversity loss. Along with many other shocking statistics, these figures show that our food systems are one of the biggest threats to our environment.

Regenerative agriculture is farming that looks after soil fertility, biodiversity, water and the wider ecosystem within which the farming takes place – a win-win for farming (a private sector) and the environment.

At Practical Action, we work with rural communities around the world to build farming systems that connect nature with people. For examples, our successful project in Kenya, which encourages young people to work in agriculture, involves the promotion of circular-farming methods; for example making manure from on-site poultry and using it directly on the vegetable patch, or using worms to breakdown organic matter and create a natural fertilizer (“vermi-compost”). Across the ocean in sub-tropical Peru, planting trees on smallholdings has brought numerous benefits for coffee bean production, the local environment and local farmers. And these are just two examples of many!

Melanio Saavedra on his coffee farm in Peru

Climate-resilient food production

Building resilience to extreme weather events is vital as we face the dramatic and devastating effects of climate change. Small-scale, farming families whose livelihoods depend on a good harvest are usually the hardest hit as weather patterns change. But by supporting small-scale farmers to adapt to the new climate realities they face, we can lessen the likelihood of failed harvests, hunger and poverty.

At Practical Action, we have prioritised climate adaptation within our agriculture and food-systems projects. In Zimbabwe, where prolonged droughts can threaten food supplies, we worked with affected communities to build sand dams to harvest water during the rainy season (sand acts as a natural water filter, preventing run-off and evaporation). We also promoted Pfumzudva, a drought-proof planting method, which was taken-up by the government and upscaled as a food security measure. Over in flood-prone Bangladesh, we introduced pumpkins that can be grown on barren, infertile flood plains, and worked with communities to create floating gardens.

Hope restored for farmers

Taking food to market and joining the dots

If we are to tackle hunger and create sustainable food systems that work for everyone – globally, it is essential to take a joined-up approach. Food security cannot be tackled in isolation; an understanding of the underlying causes of poverty, local ecosystems and environmental concerns and the social and economic factors which affect producers’ access to markets and buyers, are all essential. Through our 50-years-plus experience of working with communities in need, we are growing increasingly successful at integrating as many of these complex-but-vital strands into our projects as possible, from transforming market systems and reaching those isolated, ‘last-mile’ communities, to implementing ingenious, climate-resilient food production methods. Read more about our work below.

Sources

[i] World Hunger Facts, Action Against Hunger website, Sept. 2022 (https://www.actionagainsthunger.org.uk/why-hunger/world-hunger-facts)

[ii] The State of Food and Nutrition in the World, Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, 2021 (https://www.fao.org/3/cb4474en/online/cb4474en.html)

[iii] Climate and weather-related disasters surge five-fold over 50 years, UN News, Sept. 2021 (https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/09/1098662

[iv] ‘Does the world have enough water?’, School of International Development, East Anglia University.

[v] Global greenhouse gas emissions from animal-based foods are twice those of plant-based foods, Xu X. et al., Nature Food journal, 2, 2021 (https://www.nature.com/articles/s43016-021-00358-x)

[vi] Living Planet Report, World Wildlife Fund, 2020 (https://www.zsl.org/sites/default/files/LPR%202020%20Full%20report.pdf)