Disasters happen when people (or their assets, like buildings or farmland) are exposed to a hazard they can’t cope with.

At Practical Action we work with communities who are vulnerable to disaster risk, because they live in areas where natural hazards like floods or droughts are common, and because they lack the resources needed to prepare for and prevent the impacts.

We understand risk in a holistic way. We don’t just try to prevent or mitigate hazard exposure through hard infrastructure projects like dams and levees. These can be useful, but the reality is that every dam has a breaking point and once it breaks or overflows the consequences are disastrous.

Instead, a lot of our focus is on working with communities to find ways to thrive despite floods. We use the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities, an innovative participatory approach and tool, to help communities understand their current strengths and vulnerabilities and identify solutions that build their resilience.

Sanya and her raised poultry coop which keeps her chickens and ducks safe during the annual monsoon.

In Nepal we work with women like Gita, who since training as a cook has opened a fast-food restaurant. This second income, beyond her small-scale farming, means that were she to lose her crops in a flood (which has happened many times before), she still has an income to support her, her family, and recover her losses without getting into debt.

In Bangladesh we support farmers to raise their animal shelters so chickens and goats can stay safe during the monsoon season. Without this simple solution many farmers would lose their animals to drowning or disease every year or be forced to sell them at a loss to prevent them from dying.

Another key to disaster resilience is preparedness. People who are prepared for and know how to act when a hazard occurs will cope much better. That’s why Early Warning Systems are so important. And why they must be understood not just as hazard monitoring and communication systems, but as building risk knowledge and enhancing people’s ability to respond.

So what is an Early Warning System?

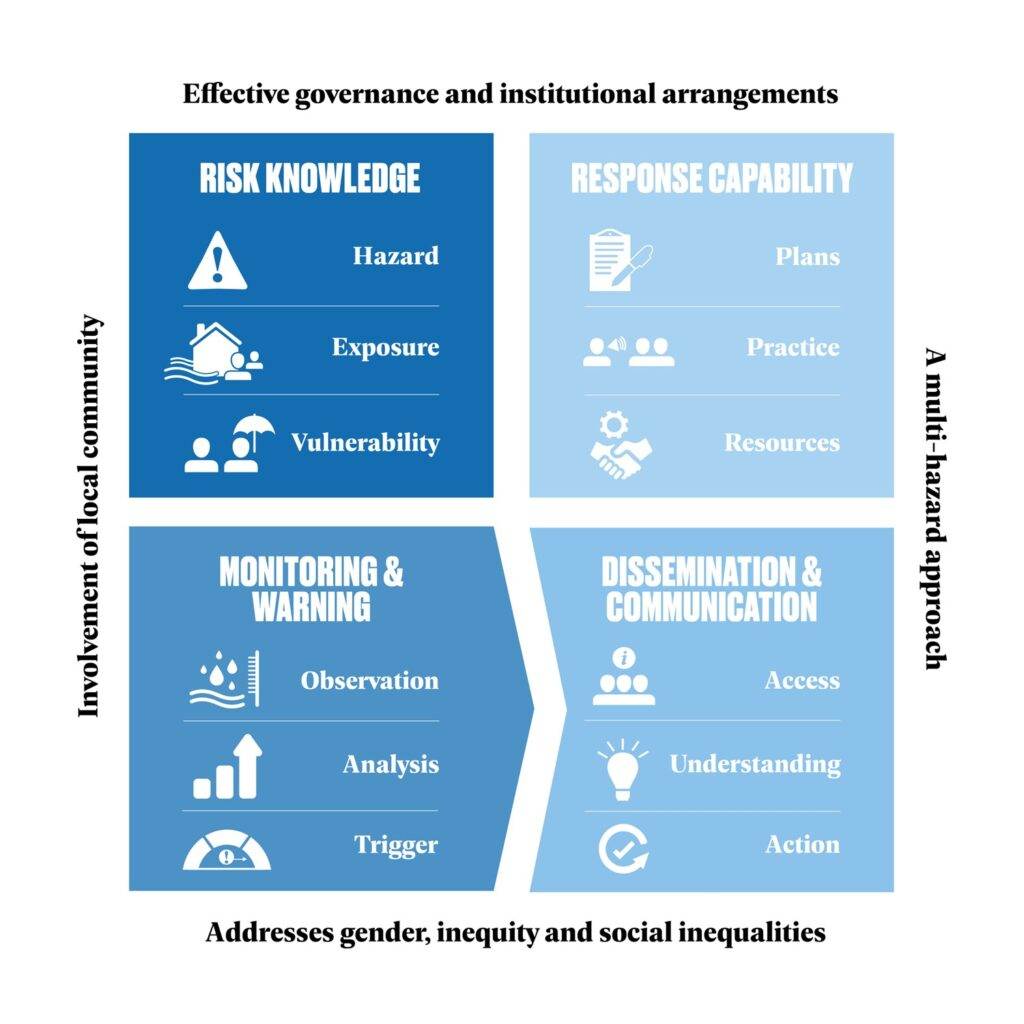

An effective Early Warning System (EWS) ensures that accurate, reliable, actionable and understandable information reaches everyone who needs it in the right way and in time for them to take action to protect themselves and other people, their assets, and livelihoods.

This graphic shows the four main elements, and four overarching components required for an EWS to be effective. We’re going to dig into each of these and give some examples of how Practical Action and our partners are working to facilitate these.

Risk knowledge

Risk assessments and risk mapping should be used to understand both where hazards are likely to occur, and where vulnerable groups and important assets and infrastructures (like hospitals and main roads) are located. Partners in the Zurich Climate Resilience Alliance have used a combination of digital mapping and community-based participatory methods to map flood risk in communities in Nepal, Peru and Mexico.

Once the knowledge has been developed it’s important that it is shared with those who need it. With the decision makers and officials who are responsible for managing risk, and with the communities themselves.

Community mapping in progress. Photo from Mexico Red Cross.

Monitoring and warning

Early Warning Systems rely on forecasting services that are as reliable, accurate, and early as possible. How early a reliable forecast, and therefore warning, can be achieved depends on the hazard. With better scientific methods and tools, and by learning from past warnings (especially where these were inaccurate or too late), the accuracy of forecasts can keep improving.

Maintenance of solar powered rainfall monitoring station in the Peruvian Andes.

Practical Action are working with a range of government, academic, and local partners to develop and improve forecasting accuracy, accessibility, and affordability. We have collected our experience and learnings from monitoring rivers in Nepal and rainfall in Peru.

Dissemination and communication

For an early warning to work it needs to reach the people who need it. And they need to understand it. Dissemination methods must be tailored to the receivers and multiple methods are likely needed. These can include tv and radio announcements, text messages, mobile apps, and in-person dissemination through loudspeakers, sirens, or colour-coded flags. The methods used must consider the most marginalised people specifically, including people who lack access to mobile phones and people who cannot read.

At Practical Action we have worked with mobile operators in Nepal to ensure that all phones in an at-risk area receive flood early warnings, regardless of network or where the owner of that phone is resident. In Bangladesh we have developed ‘voice sms’, short voice messages useful to people who cannot read.

Volunteers disseminating early warning messages in person using colour coded flags and megaphones during a flood drill in Nepal.

It’s not enough that people receive warnings, they need to understand them too. Warnings need to be in a language and phrased in a way that people understand. Messaging that focuses on impacts (such as, the flood is likely to result in these damages to property or crops) rather than hazard data (like information about wind speeds or measures of rainfall) tend to be more useful. The same is true of messaging that tells the recipient what action to take.

Response Capability

A holistic EWS incorporates response capability. That is, people’s and institutions’ ability to act based on the warning they’ve received. For this response capability to be strong everyone must have the right knowledge and skills to carry out their role effectively. These roles need to be assigned and agreed before a hazard event takes place, the Red Cross does this via a so-called Early Action Protocols that explains which agencies are responsible for implementation of what early action. Regular practice drills should be used to test (and if needed improve) the response capability.

First aid volunteers practicing safe evacuation of injured people during a flood drill in Chosica, Peru.

Community-based volunteer groups with clearly assigned responsibilities play an important role in building community capacity for responding to flood events. An approach for setting up such groups, developed by the Red Cross in Mexico, is now part of government policy for reducing disaster risk. This made a difference in 2020 when local volunteers in Tabasco played an important role during devastating floods.

Effective governance and institutions

For EWS to work well and be sustainable, they need long-term funding. It also needs to be clear, ideally through legislation, who is responsible for what aspects of the EWS and to what standards these are held.

Where governments lack the funds or expertise to deliver effective early warnings to all their citizens, the non-profit sector can, and often does, plug the gaps. But there is a risk that solutions end up piece-meal and unsustainable when dependent on external funding. Particularly in contexts where many stakeholders are involved in the EWS, coordination and communication is key to make sure everyone receives the information they need to protect their lives and livelihoods. Sadly however, not all actors have the same influence on the EWS design where, for example, aviation and agriculture are often prioritised over remote communities and informal settlements.

The District Emergency Operation Centre in Bardiya, Nepal

Local community involvement

Because the combination of local authorities, non-governmental organisations and communities know best what information, knowledge, resources and skills people need to protect themselves from a disaster, they play a key role in developing effective EWS.

But communities aren’t just the receivers of warnings, they can also play an important role in developing risk knowledge and data collection. For example, in Peru local volunteers collect rainfall data which complements official monitoring stations helping to map more localised and detailed understanding of flood and landslide risks.

Volunteer collecting rainfall data using a handmade rain gauge.

The importance of gender and cultural diversity

People of different genders have different access to early warnings. Mobile phones for example are often controlled by the men in a household. Different gender groups also interpret and respond to early warning messages differently. Women, and transgender people even more so, might be reluctant to access evacuation shelters out of fear of gender-based violence or lack of safe and dignified facilities. More examples of how marginalised gender groups experience disasters can be found in Missing Voices, while guidance on developing gender transformative early warning systems can be accessed in this report. You can also have a look at the work Practical Action has supported Baguio City in the Philippines on in order to ensure the EWS they are developing is gender and socially inclusive.

A multi-hazard approach

Hazards are complex and often happen simultaneously or trigger each other. Extreme rainfall in Nepal and Peru can lead to mudslides as well as floods.

The Red Cross Climate Centre calculated that 51.6 million people globally were directly affected by an overlap of floods, droughts, storms and the COVID-19 pandemic. In Bangladesh, communities impacted by severe floods during the height of the covid-19 pandemic struggled immensely. Practical Action utilised dissemination channels usually used to warn people of upcoming floods to inform remote communities on social distancing and personal hygiene practices to contain the spread of the virus.

Salma explained to us how receiving voice messages with flood warnings has helped her prepare for floods.

Find out more

If you want to explore the development of effective Early Warning Systems and what these require in more depth you can read the book Towards the ‘Perfect’ Weather Warning, edited by Brian Golding, with several chapters influenced by Practical Action’s work. The book is open access and free to read for anyone who wants to learn more.

This blog is based on the chapter Early Warning Systems and Their Role in Disaster Risk Reduction by the same authors.

Colleagues from Practical Action, Bikram Rana and Dharam Uprety, have also contributed to the chapter Connecting Warning with Decision and Action: A Partnership of Communicators and Users, based on their extensive experience of developing EWS in Nepal.

Author bios

Robert Šakić Trogrlić

Dr Robert Sakic Trogrlic is a research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) in Austria. He researches multi-hazards and multi-risks, community-based disaster risk reduction, and integration of local and scientific knowledge in early warning and early action.

Marc van den Homberg

Dr Marc van den Homberg leads the research activities of 510, an initiative of The Netherlands Red Cross, that supports Red Cross National Societies in developing countries with data and digital. His research concerns improving preparedness and response to both natural hazards and complex emergencies through data-driven risk assessments, impact-based forecasting, information management, and disaster risk governance.

Mirianna Budimir

Dr Mirianna Budimir is the Senior Climate and Resilience Expert in Practical Action. Her work at Practical Action includes improving the science-practice interface on topics such as disasters, early warning services, end-mile communication, gender, and international development.

Colin McQuistan

Colin McQuistan is head of Climate and Resilience at Practical Action. As a development practitioner for over 30 years he has seen first hand community based early warning systems in communities in Asia, Africa and Latin America. He is currently sharing these experience in the latest UNDRR Words into Action Guide for Multi-Hazard Early Warning Systems which will be published in the autumn.

Alison Sneddon

Alison Sneddon is a disaster risk reduction specialist whose work focuses on developing and strengthening modalities such as early warning systems, climate information services, forecast-based early action, and ecosystem-based approaches, with particular emphasis on gender and social inclusion. Her work includes research oriented towards building bases of evidence around effective practices, and the design and development of practical applications of these research findings.

Brian Golding

Brian Golding is a fellow in weather impacts at the UK Met Office. In a research career of 50 years, he has been involved in the development of weather forecasts and in their application in a wide variety of contexts. He is currently co-chair of the World Meteorological Organisation’s High Impact Weather project (HIWeather).