Loss and Damage finance is a hot topic at this year’s COP. You may have heard the term ‘Loss and Damage’ mentioned during coverage of the event, but what does it mean? And why are Practical Action pushing for fairer financial settlements for climate-related damage in Egypt this fortnight?

Read on for a ‘beginner’s guide’ to loss and damage.

What is ‘loss and damage’?

In short, it is the ‘costs’ associated with climate change. Disasters caused by climate change are resulting in irrevocable changes to our landscapes, livelihoods and day-to-day lives. The financial cost of damage to, or loss of, infrastructure, buildings, homes and jobs can be huge.

However, loss and damage ‘costs’ go much further than this and some elements are hard to quantify in financial terms. Job losses, loss of biodiversity, the loss of ancestral lands, reduction in traditional knowledge and the damage to mental health are just some examples of what loss and damage caused by man-made climate change encompasses.

How much do climate disasters cost?

When natural hazard hit, the financial cost of damage to, or loss of, infrastructure, buildings, homes and jobs can be huge. In the first ten months of 2022 alone, damage stemming from climate change-induced disasters is estimated to amount to almost £200 billion[i] (for perspective, this is more than Greece’s annual GDP[ii]). To take just one example, the severe heatwaves followed by devastating flooding in Pakistan this year has taken an estimated financial toll of £26 billion – more than 10% of the country’s GDP.

The actual cost of floods, storms, landslides, cyclones, droughts and wildfires is very difficult to accurately quantify and comprehend. The values reported are often based on insured losses, meaning the sums reported in wealthier countries are usually higher, and many other properties and assets are not included in estimates. Damage to infrastructure, buildings and homes are, of course, only one part of the picture: we cannot underestimate the value and weight of job losses, fatalities, livelihoods washed out to sea, trauma, loss of biodiversity and the irreparable destruction of natural ecosystems and cultural heritage sites.

The impact on livelihoods and individual families tends to be exacerbated in poorer countries, where insurance schemes are less likely to be place, and where local authorities lack sufficient budget to invest in mitigation measures, such as flood defences or forecasting and early warning systems. Secondary, knock-on effects are also often overlooked in financial loss calculations. Mental health scars and anxiety levels that linger in the aftermath of disasters and displacement, and the changes to family circumstances are difficult to quantify. After floods in Bangladesh for example, a rise in child labour and girls marrying underage was reported, most likely due to increased financial needs.

Who is currently paying this cost? – And who should be responsible?

In wealthier countries, individuals may rely on insurance to cover the cost of damage and material losses. When disaster strikes in less developed countries, national governments and international humanitarian organisations usually step in, but both are very overstretched and underfunded. Over the longer reconstruction period however, much of the cost of the losses and damage fall to individual households and families. For example, it has been estimated that in Bangladesh rural households spent an estimated $2 billion on climate-related disaster repairs and risk management in 2015 alone. This is 50% more than the amount spent by the government and 12 times more than what was received from international institutions[iii]. This means that much-needed income which could have been spent on food, education and healthcare had to be used on repairing damage to smallholdings and homes, replacing livestock and safeguarding homes against further flooding.

Communities which are already living close to or below the poverty line cannot foot the bill themselves. The question of who should be held accountable for climate-change induced losses and damage is really a question of global justice. With so much scientific evidence on C02 emissions and increased adverse weather, many believe that it is morally unjust for those who have contributed least to the causal factors of the climate crisis, and have the least means to deal with it, to have to bear the brunt. Campaigners for loss and damage finance cannot ignore the failure of wealthier, developed nations to act sooner in reducing carbon emissions and mitigating a crisis. This is a global emergency which calls for shared responsibility and a global solution.

We are responsible for less than 1% of the emissions that lead to climate change, yet we are experiencing a multitude of disasters due to it.Muhammad Tariq Irfan, Director of Pakistan’s Ministry for Environment and Climate Change[iv]

Why is Practical Action calling for Loss and Damage to be addressed at COP27?

For over 55 years we have stood in solidarity alongside people living in poverty, applying practical, locally relevant solutions to enable them to change their futures. The communities we work with around the world are being hit hard by the effects of climate change. Our work on the frontline has highlighted the plight of families and individuals reeling after droughts that bring hunger, and storms that wash their previous lives away.

It is the people already living in poverty who are the most vulnerable to climate-related disasters, but they cannot deal with the costs of prevention, damage mitigation and recovery alone.

The issue of loss and damage reparations needs to be prioritised this fortnight. At COP27, we are proposing a global agreement and functioning mechanisms that ensure that those responsible for climate change help pay for the damage it is causing to the world’s poorest. The climate crisis is a global problem, and as such as need to stand together and collaborate to protect future generations.

Examples from the countries we work in:

Peru:

In the Andean region of Cusco, one mountain has become a major tourist attraction. Vinicunca, or the “Mountain of Seven Colours”, has drawn many visitors in recent years, as glaciers melting revealed rainbow-like shades on its slopes. Unfortunately, glacier melting in Peru is an irreversible and fast-paced process with serious and much less colourful consequences.

Over half of Peru’s glaciers have already disappeared[v]; the remaining half is expected to vanish over the coming decades. While ice caps do renew annually, that cannot compensate for the glacier mass lost. As a result, this beautiful, unique landscape and the ecosystems that depend on it will change drastically by the end of the century. The loss of these glaciers means new lagoons will appear that could result in flooding. The Ministry of Environment has identified 500 of these as potential flood-risks this year. In terms of adverse impacts for nearby communities, these glacial melts also lead to reduced water availability during the dry season for agriculture, energy production and domestic usage, as well as the impact of rising sea levels and other significant environmental consequences which they will have to deal with.

Peru has contributed only 0.4%, yet the country now faces new challenges and bigger risks due to climate change[vi].

Kenya:

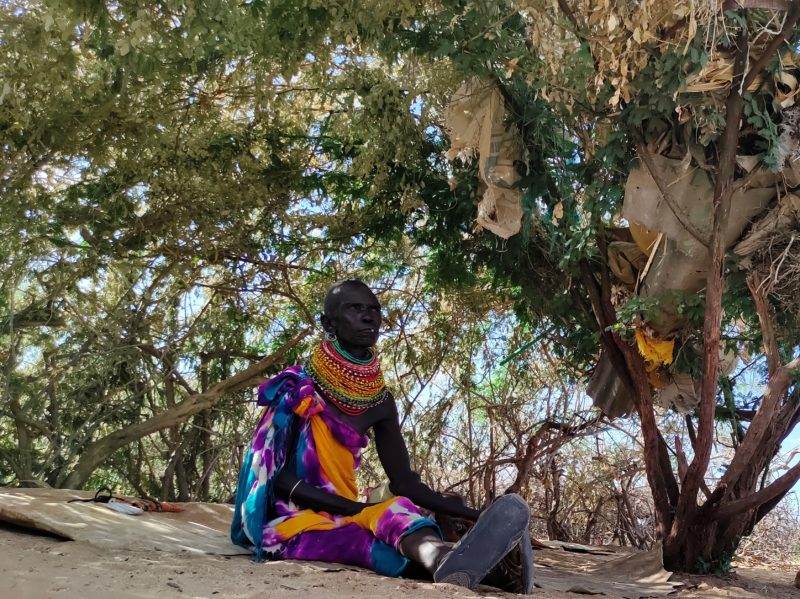

Turkana, in northern Kenya is home to approximately 1 million people. The vast majority have lived as pastoralists for centuries. Throughout this time, the region has enjoyed a long and a short rainy season, which has ensured sufficient pasture for the animals which pastoralists care for and depend on.

However, over the past three years, the region has experienced no prolonged periods of rainfall (i.e. rain for a week) and this year has seen just two days of rainfall. This has caused huge numbers of deaths amongst livestock, a catastrophic collapse of people’s incomes and wealth, and the loss of a traditional way of making a living for many families.

Now, approximately 600,000 of Turkana County’s people are reliant on food aid and are being forced to move away from the area that they call home, or look for new ways of making a living.

66-year-old Narkruk Ikadeli has recently moved home with her family. She said: There is no rain. Sometimes we can go to the town centre to find some domestic work or go to find some plants to burn to make charcoal. Animals are dying because there is no pasture. Most of the cows died and the rest were taken by bandits. That is why we came to this site.

Nepal:

Nepal is one of the most vulnerable countries to impacts climate change-induced disasters. In 2017 and 2018, a total of 968 people lost their lives to such disasters, namely floods, landslides, severe storms and fire. The total estimated economic loss during this period alone was approximately £45 million. Since then, landslides and flood have continued to occur with a high frequency, particularly in 2021 and 2022. This year, at least 110 people have died due to rain related disaster, and last month thousands of families were evacuated from their homes in western Nepal, displaced by floods and landslides.

Although the National Climate Change Policy 2019 has warned of increased climate-induced losses in the future, loss and damage is yet to be formulated into official policy. There is much to be done at national level in terms of strengthening the meteorological forecasting system and better connecting those agencies working in disaster risk reduction and post-disaster reconstruction, but budgets are lacking.

[i] Q3 Global Catastrophe Recap, Aon, Oct. 2022 (20221410-if-q3-2022-global-cat-recap.pdf)

[ii] ‘Climate change disasters cost 200 billion globally’, Tom Bawden for iNews, 9th Nov. 2022 (https://inews.co.uk/news/environment/climate-change-disasters-cost-200-billion-globally-1961874?ico=in-line_link)

[iii] ‘Bearing the climate burden: how households in Bangladesh are spending too much’, Eskander, S. and Steele, P., International Institute for Environment and Development Issue Paper, 2019.

[iv] ‘As climate disasters grow more costly, who should pay the bill?’, Alejandra Borunda for National Geographic, 4th Nov. 2022, (https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/as-climate-disasters-grow-more-costly-who-should-pay-the-bill)

[v] National Water Authority of Peru, 2020, reported in Infobae: ‘Derretimiento de glaciares formó 3.000 nuevas lagunas en Perú’, Sept. 2022, (https://www.infobae.com/america/peru/2022/09/22/derretimiento-de-glaciares-formo-3000-nuevas-lagunas-en-peru/)

[vi] Ministry for Environment, Government of Peru, Sept 2019, (https://www.gob.pe/institucion/minam/informes-publicaciones/306347-cambio-climatico-y-desarrollo-sostenible-en-el-peru)