The global health crisis has exposed the world’s vulnerability. A threat we weren’t prepared for, have struggled to respond to, and are paying a high price for. A crisis that has highlighted the thin margins on which the global economy runs – high risk ‘just in time’ systems, rather than more resilient ‘just in case’. In the midst of the pandemic the systems we rely on fell over like skittles, with hospitals overwhelmed, PPE running out, looming food shortages and economic meltdown around the world.

But while the global spotlight is focused on controlling the pandemic, it’s not the only threat we’re vulnerable to. The climate crisis hasn’t gone away. Hardly a week passes without news of devastation caused by floods, droughts, landslides and storms. With vulnerable communities facing the impossible challenge of social distancing while running for their lives.

This year the Earth experienced its hottest May on record, with temperatures in the Arctic Circle hitting 38 C. An unheard of heatwave in Siberia triggered widespread fires, and the high temperatures accelerated melting of the permafrost leading to one of the worst oil spills ever in the region. And wildfires ripped through forests from Australia to California. The future doesn’t look promising. So as governments mobilise massive resources to build back better in response to the pandemic, the questions we should be answering are whether we’re happy to settle for normal, or can we do better?

In his recent book, Disaster by Choice, Ilan Kelman, Professor of Disasters and Health at University College London brings together decades of research and unveils an uncomfortable truth – that human actions turn natural hazards into catastrophes. Disasters are created and exacerbated largely as a result of social, economic, political, cultural, and historical vulnerabilities, rather than the hazards themselves.

Disaster by Choice, Professor Ilan Kelman

In other words disasters are a direct result of decisions made without considering future risks, or those who will be hardest hit. An analysis by the World Bank (1) shows that 26 million people are forced into poverty each year as a result of disasters. The disaster-poverty cycle is vicious, unforgiving and unrelenting, borne out by our own experience. Climate change directly impacts the people we work with – from increased frequency and magnitude of floods in Nepal, through decreased agricultural yields in Zimbabwe, to water scarcity in urban informal settlements in Kenya.

‘There is change in rainfall trend. In the past the rainfall used to be regular/ continuous with low intensity. But now there are events of intensive rainfall with intermittent dry periods. It causes flood at time of intensive rainfall and drought like condition during no rainfall period’ Findings from interviews conducted by Practical Action with individuals from Janaki Rural Municipality, Nepal.

And, just as importantly, disasters are a direct result of the decisions we fail to make.

Many of the system weaknesses exposed by the health crisis, are the same weaknesses that make individuals and society vulnerable to climate change and disasters. So what must we consciously decide to change to break the ongoing cycle of disaster, vulnerability and poverty for millions and build resilient futures instead?

Building resilience requires the right information, the right capacity and skills, at the right time to shape investment decisions. Investment that is coordinated across sectors and agencies. But the exact opposite is the case, with little recognition of the value of such good decision making. Planning ahead is not a priority and not deemed an essential service.

Instead disasters are often viewed as inevitable and unstoppable, resulting in chronic under-investment in relation to the scale of the problem. Risk reduction is seen as a luxury and is not high on political agendas. And of the little money spent, barely any reaches the poorest and most vulnerable, those most in need of protection and the additional boost of development. Despite the fact that investment into disaster resilience pays off, delivering a triple dividend(2) in terms of saving lives and avoiding losses, unlocking economic potential, and delivering additional social, economic and environmental co-benefits. Even if a predicted hazard doesn’t happen.

Puja Shakya, Practical Action Consulting, Nepal

And little wonder that global systems work ‘just in time’ and not ‘just in case’, when evolution has hardwired us to react to immediate threats, but left us poor at weighing up the risks of what might happen. The result? The little money available is spent too late, and after the event – patching up what’s been damaged without addressing the mistakes that caused the disaster in the first place, and only leading to ever increasing loss and damage.

“The Disaster Risk Reduction and Management is still too ‘response focused’ such that the system gets activated when and after disaster occurs. This has resulted in the efforts being fragmented, inefficient and costly – i.e. central government led, response focused, expensive inefficient disaster risk reduction and management system. We need to change the entire system to prevent natural hazards turning into disasters.” Krity Shrestha, Practical Action Nepal

While investment in disaster response is needed, it’s outweighed by the human, environmental and financial costs of preventing them through risk reduction and mitigation. With the potential to reduce what otherwise would be the irreversible consequences of climate change.

There are no silver bullets to protect people from the impact of threats like floods or landslides. Yet entrenched views hold that large scale civil engineering alone can solve the problem. Huge concrete dams, embankments or drainage systems – expensive displays of ‘one size fits all’, top down solutions – are often imposed. Without regard for how different people live, the environment they live in, or the natural resources they rely on, essential ingredients for any solution to be sustainable and transformative.

And while these structures may represent safety, they often create a false sense of security leaving people unaware of the potential risks. So if they fail, often on a colossal scale, the effects are catastrophic for underprepared communities.

Yet investment and expectation still favor such solutions, even though they’re expensive and hard to manage locally, often just push the problem elsewhere, and fundamentally fail to tackle the underlying problems people face such as poverty, exclusion, inequality, or marginalization. While there remains a time and place for ‘big’, smaller-scale options that offer multiple benefits for people and the environment are simply overlooked.

Dharam Raj Uprety, Practical Action Nepal

The only way to build long term resilience is to start at the community level, working with individuals and their unique experiences of the risks, and who know their strengths, vulnerabilities and needs best. Yet despite this available wealth of rich local knowledge, communities are still sidelined, with little or no influence on decision making and plans – decisions made in a piecemeal manner across government departments and other external parties. Decades of evidence shows that solutions designed without considering local context and peoples’ needs simply do not work. Participation, a crucial element of sustainability, is often a mere box ticking exercise. And when it does happens, more often than not, the voices of the most marginalized members of society such as women and indigenous people, are left out.

“The authorities do not take into account the opinion of women. The mayor prefers to talk directly to men. Although women of the neighborhood have the intention to speak their mind and communicate their needs, the authorities do not listen to them.’’ Andrea, a teenager from Peru.(3)

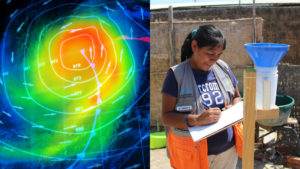

The other vital missing piece is data. In a rapidly changing world, historical weather data is of less and less use in predicting future events. Many governments lack the resources to install and maintain state of the art monitoring equipment, and localised weather information collected from things like simple rain gauges in remote communities isn’t factored in. But joined up, these offer an opportunity to massively increase the amount and accuracy of data available. Data that can make a significant difference to communities living in high risk areas, if they are supported and empowered in using it to adapt their lives and livelihoods to the changing climate.

We don’t know what future weather patterns will be, but we do know that climate change poses huge risks and has cascading impacts that are rarely accounted for. We know that local realities and the lived experiences of communities do not inform policies and planning. We know that investments made today, may be washed away by the next flood if we don’t consider future uncertainty in the design of infrastructure and social development. We’re gambling on our future, and the odds for the poorest and most marginalised people are terrible. We can’t afford to wait. The time to start building a resilient future is now.

The coronavirus pandemic has clearly exposed the need for new ways of thinking and acting. At Practical Action we know it’s possible to change the status quo, because we’re already doing it – working with communities who live at the sharp end of the climate crisis. How? Read our next article in which we’ll showcase alternative ways forward, evidenced by our long experience of doing things differently.

Dr Robert Sakic Trogrlic is Climate and Resilience Officer at Practical Action. His work focuses on building a robust evidence base for ingenious solutions to climate change that work for the poorest and most vulnerable.

Dr Robert Sakic Trogrlic is Climate and Resilience Officer at Practical Action. His work focuses on building a robust evidence base for ingenious solutions to climate change that work for the poorest and most vulnerable.

Colin McQuistan is Head of Climate and Resilience at Practical Action. He has worked extensively on issues related to the poverty-dimensions of sustainable development, disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. His main areas of interest are in systems approaches, complexity, resilience and the challenge of Climate Change.

Colin McQuistan is Head of Climate and Resilience at Practical Action. He has worked extensively on issues related to the poverty-dimensions of sustainable development, disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation. His main areas of interest are in systems approaches, complexity, resilience and the challenge of Climate Change.

Sunil Acharya is the Regional Advisor for Climate and Resilience at Practical Action. He provides technical advice and support on climate change and disaster risk reduction policy, with a specialist focus on South Asia and Least Developed Countries.

Sunil Acharya is the Regional Advisor for Climate and Resilience at Practical Action. He provides technical advice and support on climate change and disaster risk reduction policy, with a specialist focus on South Asia and Least Developed Countries.