‘Normal’ has left billions without access to modern energy

As we deal with the impacts of the coronavirus pandemic on our own lives, we rarely think about how energy (and especially electricity) facilitates so much of what we do.

You can’t have Zoom meetings if you don’t have power and without it there is no TV to entertain you during lockdowns, or fridges to store the food you have had delivered. Without electricity, authorities can’t easily transmit information and advice on virus prevention; and power is of course essential to keep hospitals running.

People without power

While globally, 90% of us have power to provide all these services, there are still 789 million people who don’t have electricity. Most affected are rural communities, especially in sub-Saharan Africa where only around 27% have access. Rural health centres, where they exist, often have no electricity, severely limiting the services they can provide to deal with the coronavirus crisis.

Furthermore, almost 3 billion people in the developing world still cook with dirty fuels. Even during ‘normal’ times, this has enormous health implications. According to the World Health Organisation, every year, almost 4 million people die prematurely from respiratory diseases as a result of indoor air pollution caused by cooking on inefficient biomass stoves and open fires. These diseases also leave people potentially more vulnerable to the effects of Covid-19 and place a burden on inadequate health services.

Under the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals, the commitment was made to address this big energy access deficit and provide universal energy access by 2030. This goal already looked unattainable pre-pandemic. Now, with the world’s poorest countries in an even more precarious economic situation and many companies which provide energy access close to collapse, the outlook is considerably worse.

In this article, we explore why ‘normal’ approaches have failed to reach the poorest and what it means for their lives.

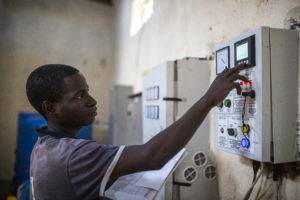

In Malawi, Steve maintains the micro-hydro power plant that uses the power of the river Bondo to provide electricity to local homes, businesses, clinics and schools.

Not far enough: Why the ‘normal’ approach is failing to connect so many

The traditional approach to providing electricity access is to extend the electricity grid linked to large (often fossil-fuel powered) power stations. However, building electricity grids is expensive and rural areas, especially the poorest and most remote ones (‘the last mile’), are often left behind by cash-strapped governments and utilities.

Luckily, there are alternative ways of providing access through off-grid renewable energy solutions. Practical Action was a pioneer in developing some of these, for example through community micro-hydro schemes in Kenya, Nepal, Peru, Zimbabwe and Malawi. Hydro isn’t possible everywhere, but wind and biogas are other options. In recent years, cost reductions have made off-grid solar photovoltaics (PV) particularly attractive.

Under current and planned policies (even before the start of the coronavirus crisis) it’s estimated that in 2030, 620 million people will still not have electricity access, 85% of them in sub-Saharan Africa. For many communities in remote locations, this means another generation or more of being left behind.

“Most people in Southern African Countries live in rural areas and don’t have the energy access they need to make their lives better. Without energy, agricultural production is low, healthcare is poor, education quality is compromised and women and children face a number of difficulties just to cook a single meal”

Zibusiso Ncube, Practical Action, Zimbabwe

Not on the radar: Clean cooking remains the Cinderella of energy access

As for clean cooking, it rarely even appears as a priority on the agendas of national policy-makers.

In Sudan, Aesha’s health has improved since she started using a low-smoke stove instead of burning wood.

International donors have also put much more emphasis on electricity access. And without public support, companies struggle to provide stove and fuel at prices the poor can afford. It is therefore not surprising that clean cooking has long been chronically underfunded, with both public and private funding falling far short of what is needed.

According to SEforAll, only USD 32 million is being invested into clean cooking per year, a fraction of the USD 4.4 billion (just USD1.6 per person) needed per year to close the access gap.

And even those most affected attach less priority to clean cooking than electricity access, as demonstrated by research for our Poor People’s Energy Outlook (PPEO). Reasons for this are complex but include lack of awareness of the health impacts of cooking with dirty fuels and less value being attached to women’s work, such as collecting and chopping firewood and cooking.

Solutions are also more complex than for electricity – they include improved biomass cookstoves, biogas, bioethanol, LPG and even electricity. The most appropriate options can vary from place to place, with affordability often a big challenge. Nevertheless, our programmes in, for instance, Sudan, Kenya and Nepal, have shown how behaviour change campaigns combined with support to catalyse clean cookstove and fuel market growth can lead to widespread adoption of clean cooking.

“Household air pollution due to cooking with dirty fuels is one of the leading factors in premature deaths in Nepal and claims more than 22,000 lives annually—mainly women and children. The coronavirus pandemic has worsened the situation. As male migrant workers have returned, the workload of many women has increased, adding extra hours spent cooking and increasing their exposure to harmful air pollutants.”

Pooja Sharma, Practical Action, Nepal

Not meeting real needs: Lack of energy access leaves few options

In the PPEO, we also highlighted that energy access programmes too often focus on supply only, without regard for what services people need and how they would use the energy to improve incomes and living standards. The voices of energy-poor people are often left out of decision making.

Boosting electricity uses beyond household consumption and developing business opportunities makes electricity more affordable and sustainable in the long-term. In rural off-grid communities, most people rely on subsistence farming. Electricity is needed for pumping, irrigation, milling, threshing, post-harvest storage (refrigeration) or adding value through food processing. Also, poor communities want services such as street lighting and power to community services like schools and health facilities.

Another group whose energy needs rarely make the headlines are refugees and internally displaced people. More than 70 million people around the world are forcibly displaced, and the provision of energy to them is often inadequate, inefficient, or unsafe. Lack of access to affordable energy stops refugees from being able to rebuild their lives and keeps them reliant on aid.

Through our Renewable Energy for Refugees project, we have been working with refugees in Rwanda and Jordan where communities struggle to access affordable energy to power their homes, cook meals, earn an income, light the places where they live, and run schools, health clinics, and public toilets.

“I believe that if there was electricity in this camp my business would grow. That would mean better opportunities for me and my son. I would be able to pay for him to get a good education and have a brighter future.”

Chantal, a tailor in Gihembe refugee camp, Rwanda

Not sustainable: Why current business models don’t work for the ‘last mile’

Analysis indicates that off-grid systems (a mix of mini-grids and stand-alone systems) would be the least-cost solution for many unconnected people. Yet, many governments continue to focus on-grid electricity which they subsidise, while expecting the private sector to supply off-grid systems and users to bear the full cost, with only 1.3% of overall electricity access funding going to off-grid renewables. As these communities are also amongst the poorest, affordability of even the most basic services is often an issue.

In Europe and the United States, rural electrification required significant amounts of public funding. Considering the high levels of poverty in most unconnected communities, it is unrealistic to expect off-grid rural electrification in developing countries to proceed without a similar funding approach. Subsidies need to be smart and sustainable to address long-term poverty challenges.

Once communities have modern energy access, and markets for off-grid products have grown to the point where economies of scale can be achieved, they are able to develop income generating activities, but they need a helping hand to get over this bump in the road to better lives and livelihoods.

Coronavirus has made ‘normal’ even worse

Pre-pandemic, the energy access situation had actually improved significantly, at least for electricity. More than a billion people gained access to electricity over the last decade, at a much faster rate than in the previous decade. In many places, this access has been provided by companies offering solar PV systems through Pay-as-you-go business models. Pre-pandemic, the sector was booming with the off-grid solar sector association GOGLA reporting record-breaking sales in the second half of 2019.

The crisis has had a devastating impact on off-grid solar companies, clean cookstove and fuel companies, including last mile distributors, as well as the wider energy access sector. Companies have been struggling to access supplies or to reach customers; commission-based employees are unable to earn a living wage; and with customers unable to afford products, the financial viability of many companies is threatened.

A survey by EnDev published in August 2020 of 613 off-grid energy companies in 44 countries, revealed that 85% of companies will struggle to survive more than 5 months. At the same time, 69% of members of our Global Distributors Collective have reported reduced sales and 17% have ceased operations altogether.

Entrepreneurs making and selling low-smoke stoves have had their businesses damaged by the pandemic.

Failure of these businesses would be disastrous not only for the companies and their employees, but also for many who rely on them for current or future energy access. Even those who can still afford it will be unable to access energy products and services if suppliers have gone out of business. Few companies have received any support and there is an urgent need for short-term grant relief.

When the immediate effects of coronavirus have ebbed, the economic impacts will carry over into shrunken markets, with customers having less money, fewer companies and those which survive having less funds to invest.

How do we go forward from here?

As coronavirus (we hope) recedes, stimulating economic recovery to create employment, boost incomes and demand, while also providing infrastructure and building human capacity to support longer-term growth, will become the priority. At Practical Action we believe that there are opportunities to ‘build back better’, with stimulus investment that harnesses the transformational power of clean, affordable energy.

To achieve this, we need:

- Holistic approaches – Energy planning and financing needs to give equal emphasis to grid, off-grid, and clean cooking, and consider synergies between them. This should involve multiple ministries to develop productive and community uses of energy, and to ensure energy access achieves its transformational potential.

- Increased public funding – There is a crucial role for public funding in reaching energy-poor people, particularly in off-grid electrification and clean cooking, which cannot be left to the market alone.

- Addressing of demand, not just supply – Traditional approaches have often focused on the energy supply. However, increasing demand, for example through developing productive uses of energy, is critical to the uptake and sustainability of solutions.

- Championing of women’s inclusion – Gender mainstreaming is needed to ensure that the issues women prioritise are addressed, and that women are empowered to participate at all levels of energy value chains.

- To ensure no-one is left behind – Programmes need to be pro-actively designed to reach the ‘last mile’, with sufficient resourcing and skilled staff.

Read our next article in which we’ll demonstrate some of these opportunities, evidenced by our long experience of doing things differently.

Ute Collier is our Head of Energy and Mary Willcox is our Senior Energy Strategy Advisor. They work out of our UK office.